| ||||

Inside The Race To Become The Chipotle Of Pizza

Wednesday, August 10, 2016

Carl Chang smiles widely as he approaches me in the sprawling parking lot of the Irvine Spectrum, a giant outdoor shopping complex in Southern California. We head toward the busy restaurant he opened a few yards down, which, depending on whom you believe, may very well represent the future of pizza in the US.

Chang's mission is to lure America's delivery-addicted pizza eaters back into the pizzeria by way of a gourmet product made before their eyes at lightning speed.

Nothing about Chang suggests he should be at the vanguard of a pizza revolution. The 47-year-old father of four still has a full-time job as CEO of a real estate business; the restaurant was meant to be a hobby. He never went to culinary school, and has never worked at a pizza joint.

If the name Carl Chang rings familiar at all, it's probably as the older brother and coach of Michael Chang, who in 1989 became the the youngest male player to win a Grand Slam singles title, taking the French Open when he was just 17. Michael was called "a prodigy" and multimillion-dollar endorsement deals came his way, all before he was old enough to buy a lottery ticket."I've always been the guy that has the famous brother," Chang says. "I always joke about changing my name on my birth certificate to Michael Chang's Older Brother." But in just five years, Michael Chang's Older Brother has begun to build a name for himself. In 2015, Pieology rang up $80 million in sales across all its restaurants, and it expects sales to hit $225 million in 2016. Blaze's sales surpassed the $100 million mark last year, while Mod took in $65 million."Everyone feels like this is the next big category," says Rick Wetzel, founder of Wetzel's Pretzels, who launched Blaze Pizza in 2012 with his wife, Elise. Data from Technomic shows that while sales at regular fast-food pizza chains grew by 5.3% in 2015, sales at higher-end fast-casual pizza chains grew by 36.7%. They're designed to be attractive for walk-in customers and the lunch crowd, and they aim to churn out a pizza as quickly as fast food's speediest options, having adopted Chipotle's and Subway's build-your-own, assembly-line model.

It gets shredded in-house: "It has to be a certain length and a certain width." Chang also developed Pieology's sweet, herby, ever-so-subtly spicy red-sauce recipe over a year and a half. "Tomatoes are so different. Oh my goodness. Some tomatoes are sweeter, some are richer, some have no taste whatsoever. Some you can tell weren't vine-ripened," he says. "You just can taste it." Nodding to a trend taken mainstream by Chipotle and other fast-casual restaurants, Pieology and its peers all pay particular attention to the provenance of their ingredients. Customers will find such hyper-self-aware ingredients as "California, non-GMO, 50-year-old seed-stock roasted garlic" at Blaze, and flours that are "never bleached and never bromated and have no unnecessary chemicals" in Mod's dough. "It is time to make it work for the lifestyles of here and now," says Ally Svenson, who in 2008 co-founded Mod with her husband, Scott, formerly the president of Starbucks in the UK. For Svenson, pizza "has been around forever and will be around forever, but what works for us now is different from what worked for us before."

"Chipotle paved the way for the idea that just because it's fast, it doesn't have to be a typical fast-food experience," says Lachlan Mackinnon-Patterson, a co-founder of Pizzeria Locale. In the same tenor as Chipotle's executives, the chef explains that his vision is to "change people's pizza habits at a broad scale and change how people thought about fast-food pizza. "To win the office lunch crowd, a chain needs to make a plausible case that it's selling a food that is okay to consume on a semi-regular basis - and that's one major roadblock for the new pizza chains. The National Institutes of Health specifically names pizza among foods teens should avoid, along with candy, soda, and fast food, which "have lots of added sugar, solid fats, and sodium," the site explains. "A healthy eating plan is low in these items."We're still at home plate with that," Mackinnon-Patterson acknowledges. "I don't even know if we've left the plate, really. We're just starting to walk to first base."

The kind of pies favored by new-school chains like Blaze and Pieology fall somewhere between traditional Neapolitan pizza and the anarchy of the big American chains.

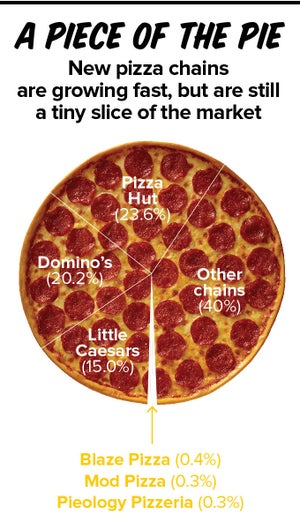

Today's young consumers, Chang believes, "want to control how the pizza is made, the toppings, the quality, the execution. "And we threw a twist on that: Instead of being charged per topping, why not create a model where you have so much control over how you want to build your own pie, and the freedom to do so limitlessly all for one price? And we actually pulled it off." Despite all the hubbub about artisanal toppings and customization, it's the Neapolitan-style cooking times that define the new-school pizza joints. It turns out that while most Americans have gotten used to waiting half an hour to have their pizza delivered or served to them by a waiter, pizza is an ideal product for a fast-food lunch: An authentic VPN-certified margherita pie can cook in one minute. The new-school pizza chains see this ability to turbo-bake as central to making quick grab-and-go pizzas available to the lunch-hour masses.Whether or not one of these franchises manages to become the Chipotle of pizza, their formula seems to be working. The average franchised Pieology makes $1.3 million in sales per year. Blaze restaurants take in about $1.5 million each.It's far exceeded any expectations Chang may have had when he promised his wife, Diana, he would just open one location by Cal State Fullerton in 2011 while he continued to run the real estate company. Sitting in their dining room at home, Diana recalls how years ago she said, "This is your dream; let's just do it. We'll have fun." Carl Chang laughs wildly. She said, "Just one, right?" - Yet as competing chains like Blaze expanded in the LA area, he says, a deep instinct nurtured during his days in tennis was revived: "The competitiveness turned on." But even Michael Chang knows that competitiveness only goes so far. "We've seen quite a few tennis players open up restaurants," he says. "It's a tough business. We've seen a lot open and a lot of them close. If [Carl] had said, "Hey we want to open up 100 stores within five years, - I'd probably be more hesitant. But he had the mentality of, "Hey, we just want to open one store first and see how it goes." I think that's reasonable." Meanwhile, Pizza Hut's US store count declined by 41 in 2015. Still, the biggest losers last year were independent pizza restaurants, which have been struggling against chains old and new.

Pizza Hut spokesman Doug Terfehr said that unlike the fast-casual competitors, which rely on walk-in traffic, Pizza Hut is a full-service restaurant and a delivery business, and "we feel that customers recognize that difference." Yet even Pizza Hut announced in 2015 it will update 700 stores each year through 2022 to keep up with trends, and roll out new ovens that - like those at the new fast-casual chains - can cook pizza in three minutes. Even if the new fast-casual chains are still a minuscule part of the of the $38 billion US pizza business, they have attracted plenty of attention from investors. Mod to date has raised more than $100 million, while in 2015, Blaze added LeBron James to its roster of investors (James decided not to renew his endorsement deal with McDonald's). Earlier this year, the 1,900-store Chinese fast-food chain Panda Express announced that it had bought a minority stake in Pieology. All that money being thrown around means tough competition, especially for these three chains, which all offer similar menus, prices, and experiences. After all, how many different ways are there to be the Chipotle of pizza? Pieology has fallen behind Mod and Blaze in terms of store count - and then there are the 30-plus other chains fighting for their share of pizza dollars. The long-term challenge for the new fast-casual pizza chains will be facing off not only against the thousands of pizza outlets already opened by the established giants, but also the other fast-casual chains that have nothing to do with pizza at all. "We compete for the same market share as the burger brands, and Panera and such," Chang says. "We tend to be great co-tenants, because we tend to be drivers for the same dayparts and similar consumers."Chang watches as customers nosh on their customized pies. He may be at the vanguard of a pizza revolution, but Pieology has reached a point where Chang needs more than the 37 people now working at headquarters to manage the next phase of expansion. The founder will eventually have to shift some of his executive powers to other people he trusts. "I really don't want to be the forefront of the brand," he says. "I'd rather stay behind the scenes. I'd rather be the unknown face and let Pieology stand on its own. That's always been my comfort zone. I grew up that way; I've always been behind the much more famous brother. I'm okay with that."

Pieology News and Press Releases

This article has been read 2006 times.

Would you like to own a Pieology Franchise?

For more information about becoming a Pieology Franchise owner, including a franchise overview, start-up costs, fees, training and more, please visit our Pieology Franchise Information page.

Updated Recently

Updated Recently